The

Maori People and Their Legal System

Alissa Strong

May

2006

Introduction This

paper is based almost entirely upon two sources: the first is a book entitled

Primitive Economics of the New Zealand

Maori by Raymond Firth,

[1] and the second

is a webbed book called

A Glimpse into the

Maori World: Maori Perspectives on Justice a collaborative work

coordinated by Ramari Paul and comprising a number of papers on individual

topics written by students and professors at several local

universities.

[2] One of the interesting things

about doing this research is that there is some degree of disagreement as to the

extent of communism in pre-European Maori culture. I found that

Primitive Economics generally takes the

perspective that although much of Maori concepts of ownership were communal,

that they none-the-less had a well developed concept of personal ownership and

individual use.

[3] In the webbed book, however, I

found a distinctly different attitude on ownership which tends to downplay the

importance of personal ownership in favor of a view of the Maori as

intrinsically and almost uniformly communist.

[4]

As a result of the fact that Firth takes into account the scholars and experts

opinions that communal living was prevalent but

still finds strong evidence for some

aspects of individual ownership, I tend to weight his analysis as more

authoritative on point. This is particularly true because the webbed book makes

very little reference to any personal items and spends no time analyzing the

possibility of personal ownership.

I. Maori

People and Culture

A. History

and Background

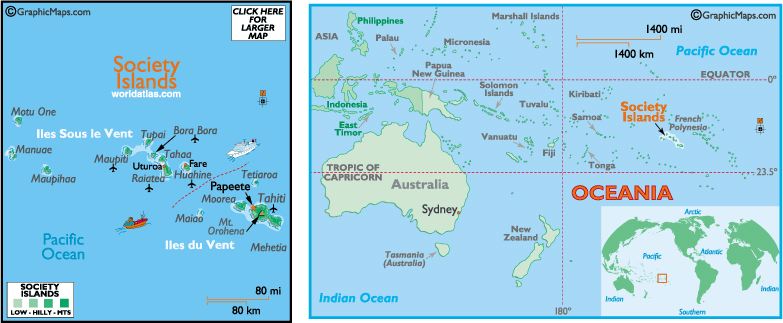

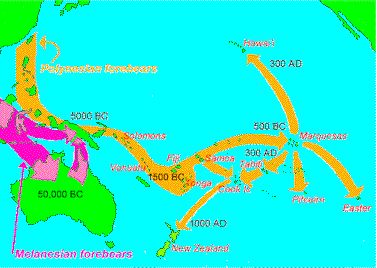

Possibly as early as 2000 years

ago, ancestors of the Maori left southeastern Asia and settled in the Society

Islands, located particularly Ra’iatea, near to Bora Bora and

Tahiti.

[5] The people were Polynesian, ethnically

similar to other indigenous peoples of the south pacific including those of the

Hawaiian islands.

[6] When fishing expeditions had

discovered “new lands” to the south, centuries of warfare in a

struggle for space, power, and food influenced the less successful chiefs to

lead their people to the Aotearoa, the North Island of modern day New

Zealand.

[7] Thus, in giant, sea-faring canoes

called

waka, capable of holding up to

one hundred passengers in addition to plentiful supplies, Maori ancestors

arrived on Aotearoa as early as 800 A.D.

[8] When

the bulk of the Polynesian settlers arrived in the fourteenth century and found

other people already inhabiting the North Island, they mostly absorbed, but

sometimes enslaved them into their culture.

[9]

All of the modern day Maori are descended from this mixed group of earlier

Polynesian travelers.

Physically the Maori are a

tall, well-built, tough race. Women are strong, curvy, easily bore children, and

sometimes even accompanied men to war.

[10] Well

versed in language and knowledge of natural

surroundings,

[11] the Maori were avid observers

of the sky and the stars .

[12] They saw the

constellations (sometimes in similar groupings as European traditions) as

“guides to man,” giving signs regarding fertility, crops, fishing,

navigation, migration, and weather changes.

[13]

The Maori calendar, which began in June, was a twelve month lunar cycle

responsible for guiding Maori economic activities such as planting, harvesting,

and gathering of the essential dietary

items.

[14] What is different about the Maori

calendar, however, from other lunar calendars such as the one used by Muslims,

is that occasionally the calendar incorporates a thirteenth month, most likely

because the calendar needed to predict the weather cycles, which would have been

slightly off had not the thirteenth month sometimes been

included.

[15] One way to distinguish between

the tribes is to divide them by the food they

ate.

[16] Generally, nearly all tribes had more

than one main food source.

[17] The fern root

was a particularly common staple for most of the tribes, though the coastal

eastern tribes relied more upon fish for basic dietary

needs.

[18] “In general the tribes of

Auckland and the North, the Bay of Plenty, Tauranga and the remainder of the

East Cost, Taranaki, Nelson, and the Kaiapohia district practiced agriculture.

The people of the West Coast and the larger part of the South Island, as also

Taupo and Urewera, gained their living chiefly from forest products, augmented

largely in the case of Whanganui by

eels.”

[19] The Arawa tribes main food

source was freshwater fish, crayfish, and mussels from

lakes.

[20] B. The

Maori Village:

Kainga and

Pa

Pa

is the term used to describe villages protected by way of natural situation or

constructed reinforcement.

[21] The term

Kainga is used to describe villages

which are not protected like the

pa.

These are the only types currently inhabited by

Maori.

[22] In both types of villages, the

internal structure was essentially the same, each village having some number of

randomly patterned “rectangular dwelling-huts” of approximately ten

by twelve feet, constructed out of a variety of materials including, poles,

thatch and sometimes timbers, usually lined with reeds or ferns to ensure

warmth.

[23] In addition to dwellings, each

village had a social gathering building, communal underground storehouses and

pits for food, communal cooking sheds, a common latrine, a sacred alter or

tauhu, and a public square or

marae.

[24]

Despite the lack of a planning pattern in the dwellings’ locations, the

chief’s dwelling was often the farthest from the opening or gate of the

village and the dwellings were roughly arranged around the

marae.[25]

In addition to the dwellings were one or more larger “houses of

superior style” for social meetings and

gatherings.

[26] Food in villages was communally

in underground pits or storehouses. As the dwellings were primarily for

sleeping, the communal “cooking sheds” were weak buildings, often

open to the elements or only partially walled with firewood since in good

weather cooking was done outdoors.

[27] As for

sanitation, Maori villages usually utilized a common latrine either near the

edge of a cliff or outskirts of the

village.

[28]

The

marae¸ a large open space or field

in the middle of the village was the center of Maori life, a playground,

meeting-place and dining center of the

village.

[29] Aside from the marae, a

visitor’s gaze would be first drawn to the

whare runanga or larger meeting house

of the village, the construction of which was a communal economic effort

completed by a complex exchange of goods and

services.

[30] One of the ancient customs

prevented food from being brought into or consumed within the

whare

runanga for fear of upsetting the

tapu or sacredness of the dwelling and

the people.

[31]

Tapu could also be disrupted by the

wearing of footwear within that building. In modern times, however, the law

preventing food consumption seems to have been

weakened.

[32] Further, although the Maori still

observe the no-shoe policy, visitors may choose to keep on their footwear so

long as they submit to a heavy fine to offset the damage to the

tapu of the

building.

[33] C. Families,

Kinship, Marriage and Children

1. Families

and kinship

The smallest grouping in a Maori

culture is the

whanau, a grouping of

closely related family members that usually cohabit in one or two dwelling huts

or

whare.

[34]

This group usually comprised two elderly people, their children and

grandchildren or it could describe siblings and their spouses and

children.

[35] As a unit of social and economic

affairs within the village and tribe, the

whanau was independent and self-reliant

under the direction of the male head of the

household.

[36] The next largest Maori social

grouping is the

hapu, an extended

kinship group or clan.

[37] Over several

generations, as a

whanau grew in size,

it could eventually become large enough and important enough in rank to be

termed a

hapu.[38]

At this stage the

hapu, usually

attaining several hundred in membership,

[39]

named themselves after a noteworthy common

ancestor

[40] and began actively encouraging

endogamy (marriage within a clan or group) of distant relations within the

clan.

[41] Since endogamy was not required,

though, when a person from one clan married one from another, the children were

actually considered members of both

hapu,

[42]

in much the same way that a child with parents from two different countries

might have dual citizenship. And although a child could choose to be a member of

either this mother’s or his father’s

hapu, it seems to have been common

practice to trace one’s lineage to the most important patrilineal

relative.

[43] Further, though a married couple

from two different

hapu could choose to

live in either of their villages, once chosen, if their descendents remained in

the same

hapu, over several generations

the children would no longer consider themselves members of the

hapu from which their one ancestor

came.

[44] The next largest social grouping

was called an

iwi and usually consisted

of several larger

hapu, and perhaps

some smaller

hapu.

[45]

In some sources,

iwi are considered

synonymous with “tribes.”

[46]

Generally, villages were inhabited by one

hapu, or if the

hapu were smaller than usual, a village

might be home to two or three clans.

[47] Even

if the village was entirely the same

hapu, there were always village members

who were not related as a result of intermarriage or

visitors.

[48] The word

iwi literally means “bone”

and refers to the bones of the ancestors of the

iwi.

[49]

Further, in addition to their genealogic requirements

iwi were independent geographic units

identified by their territorial boundaries which they defended, when necessary,

by force.

[50] As an independent socio-economic

unit—and the largest of such units in Maori culture—an

iwi was responsible for protecting its

member’s interests and for enhancing the

mana[51]

of the whole.

[52] Aside from the

whanau, the

hapu, and the

iwi, the fourth and largest social

grouping among the Maori was the

waka,[53]

the group of people who could trace their common ancestors to crewing one of the

famous fourteenth century canoes.

[54] Unlike

the

whanau,

hapu or

iwi,

waka groupings are not necessarily

geographic since they incorporate such a large number of individuals.

Apparently, modern day Maori are taught from which

waka they come and hold the association

with pride, though they do not live in such groupings (Firth, 101). One modern

Maori, for example, belongs to the Takitimu and Kurahaupo

wakas and the Ngai Tara, Ngati

Rangitane, Ngati Kahungunu and Ngai Te Whatuiapiti

iwis.

[55]

Because the

waka involved such a large

group, the ties between

iwi from a

common

waka were not as strong as the

ties between

hapu of a common

iwi; in spite of this, the

waka bond served as an intertribal

alliance binding the

iwi in common

defense in times of war against other

iwi or

waka.

[56]2. Marriage

It seems that marriage was

generally monogamous and regarded, much the same as cultures around the world,

as a lifelong partnership.

[57] Despite the

belief that marriage was for life, divorce and separation were

available.

[58] Maori marriages began with a

definite and explicit marriage ceremony and were sexually

exclusive.

[59] Adultery or

puremu was defined as sexual

inclusivity among anyone outside the husband and wife and was severely

punished:

[60] Puremu outside of the hapu or

iwi was considered even more serious

than inter-hapu adultery and consequently “redress was sought by the

injured

hapu [the hapu of the husband

of the adulterous woman] sending a [war] party to confront the whanau and hapu

of the woman who had transgressed her

marriage.”

[61] Once there, the war party

would exact reparation through confiscation of prized treasures

(

taonga) such as greenstone sculptures

or amulets. Both parties to the conflict considered this the resolution of the

dispute, though the female’s

hapu

did not get to exact any punishment on

anyone.

[62] Further, it is not clear whether

the war parties ever used violence to exact restitution on the offending family.

Though most cases of punishment for adultery punished the woman and her kin,

some, though few, placed the blame upon the man with whom she was involved: In

one instance the male involved in the adultery was killed by the female’s

brother, but this was considered just punishment for his adulterous

action.

[63] And, although adultery was a

serious offense, there were times in which neither party was

punished.

[64] Though often economic and

political alliances, marriages were also united by love and affection in most

cases and fidelity, particularly on the part of wives, was

coveted.

[65] And, although the nuclear family

was not given much weight as a unit of tribal society, the marriage partnership

was recognized, respected and given a small degree of independence from the

whanau in matters relating to the

married couple alone.

[66] Marriages were often arranged as

a means of maintaining tribal lands and heirlooms: this was established

primarily through the naming of female children by important relatives.

[67] Supplying the name for the child seems to

have conferred upon the relative a guardianship right in her

marriage.

[68] In one case a girl was named

Rangi-hua-moa at the request of chief Takaanini and was ultimately marred to a

young relative of the chief.

[69] In addition to

many arranged marriages, those that were not, required parental and sibling

(particularly brotherly) consent.

[70] The basis

for familial consent was not in control over women so much as it was founded in

contractual concerns: if a woman married a stranger and non-member of the tribe,

her children would still inherit partial ownership rights in her family’s

tribal lands and as a result, her brothers who’s children would be

impacted by such an arrangement had the right to

intervene.

[71] Although no specific age is

given as the marriageable age, it is clear that by age eighteen, if not sooner,

a woman had come of age for the purpose of

marriage.

[72] And, although it is not clear

whether it was rule or custom, serious dating did not happen before about age

fifteen.

[73] Physical maturity was the primary

determinant of eligibility for marriage, though most women married before age

twenty while most men married after.

[74]

Further, it was discovered early that close intermarriage weakens offspring and

therefore endogamy was encouraged only so far as it did not involve marriage

between relatives closer than three

generations.

[75] Though marriage was generally

monogamous, chiefs sometimes married multiple wives. In such cases, the chief

and first wife would be of equal social status and would be charged with

responsibility for the domestic household

affairs.

[76] Additionally, it was common for

men in polygamous marriages to have several separate homes and to live

consecutively with each wife, particularly in cases where the wives could not

cohabit peaceably.

[77] Secondary wives were

often either slave girls or sisters to the primary wife, though this was by

custom, not rule.

[78] One of the reasons for

allowing such polygamy in spite of the cultural standard of sexual exclusivity

was routed in the belief that infertility was unique to

women.

[79] Another may have been to counteract

the slight discrepancy in the ratio of men to women owning to those men killed

in warfare.

[80] 3. Children

and Adoption

Because of the prevalence of

adoption and the emphasis on the

whanau

and not on nuclear families, some Maori scholars have suggests that there is

little evidence of affection between parents and

children.

[81] Firth, however, asserts ample

evidence to the contrary suggesting a great deal of “deep affection”

and “excessive fondness” among parents and children in Maori

tribes.

[82] Further, evidence of particular

customs to be practiced by expectant mothers demonstrates Maori recognition of

the important connection between mother and child. Maori lore connected

children’s stunted growth with the practice of cutting a pregnant

woman’s hair and thus proscribed the

activity.

[83] Maori awareness of the important

mother-child bond is further evidenced in a funeral lament’s recognition

that mothers are the ones who look forward to their children’s homecoming,

who shelter and comfort their children, and who inquire as to their

children’s safety and wellbeing.

[84]

Child-rearing was not just the purview of mothers, however, and fathers usually

took an active interest in the child, even before being

born.

[85] Fathers were responsible for sating

the food cravings of their pregnant wives, for carrying around the newborn,

washing the child, watching the child while working, and for educating the male

children.

[86] In addition to natural born

children, Maori custom provided for frequent adoptions.

[87]What is different and interesting about

Maori adoption is that its purpose seems have been not, as in American and

European cultures, to place an unwanted or unaffordable child into a good home

but instead to regain and strengthen family ties weakened by distance or travel.

To that end, adoptions took place only between relatives, but never

intertribally or with strangers.

[88] To better

understand this custom, the story of Te Pataka Te Hapi is illustrative: Te

Pataka Te Hapi lived in one place (Hauraki) but was from another (Taranaki). In

moving from Taranaki, he had lost his right his land there. To effectuate a

reconnection and regaining of the right to those lands, Te Pataka Te

Hapi’s grandson was named Wananga after a cousin’s father which

subsequently gave the cousin, a resident of Taranki) a right to the child.

Wananga (the child) was adopted at age three by his cousin and went to live in

Taranki.

[89] Though in this case, Wananga was

taken away from his tearful mother at age three, sometimes the departure did not

occur until the child came of age and was marriageable. This was particularly

the case for girls who were promised in a form of marriage arrangement by their

names given at birth but were only sent for later when they were to be

married.

[90]D. Social

Stratification and Structure

There

were primarily three classes in Maori social structure: rangatira, tutua,

taurekareka. (chiefs, commoners and

slaves.)

[91] In addition to classes, further

distinction called

“

tohunga” was applicable,

regardless of class, to any person expert in a skill such as wizardry, black

magic, tattooing, carving, warring, or any other area of knowledge and

ability.

[92] The

tutua class was the largest in Maori

communities and represented the most economically productive group in the

community.

[93]

Tutua, translated in English as

commoners, are defined as a class by their not being apart of the chief class or

those who are high born. The division between the chiefs and commoners occurred

as a result of first born children being of higher class than those born later.

As a result, even though a

tutua might

be able to claim a blood relationship to the founding ancestor of the group, if

he or she were not apart of the senior line, the line of first children, they

could not be apart of the

rangatira

class.

[94] Additionally, as junior family

members married other junior family members, their rank diverged even farther

from the

rangatira class, a process

that sometimes resulted in these junior members breaking away and forming their

own hapus.

[95]

The slave class, on the other

hand, were generally comprised of those captured from Maori defeated in

battles.

[96] Because uncaptured members of the

slaves tribes and families did not attempt their rescues and generally thought

of them as dead, slaves were not restricted since they had no one to whom to

return.

[97] Further, slaves, unlike a lot of

the rest of Maori property, were individually owned and never the property of

the general tribe.

[98] And, though there were

no specific rules requiring slaves to obey their masters, relations between them

were relatively peaceful because slaves were fed and housed and insolence or

disobedience could result in their use as a human sacrifice at the preference of

their master.

[99] As for their tasks, they were

responsible for menial jobs and things that would affect the honor of the other

classes.

[100] For example, dull and

unpleasant tasks such as drawing water, carrying firewood, bearing food or

supplies, cooking, and paddling the

canoes.

[101] Interestingly, offspring of a

slave with another social class elevated the children into the

tutua class, though it is not clear

just how commonly this occurred.

[102] Primogeniture

being of the utmost importance in Maori culture, the line of descent through

eldest sons, called “

aho

ariki,” was the established method of choosing tribal

chiefs.

[103] Chiefs came from long lines of

chiefs and their descent was the primary factor in their prestige and

authority.

[104] The

ariki or first born son of the highest

ranking family was the leader or chief. The highest ranking family was

determined by the family able to trace its genealogy from the founder of the

iwi or

hapu through the most related first

ancestors.

[105] Younger siblings of the

ariki were

rangitira as well. Further, first-born

girls, called “

ariki

tapairu,” though not chiefs, had ceremonial and ritual

responsibilities on account of their

birth.

[106]

For the

ariki, however, birth alone was not

enough to guarantee becoming a full chief: personality, foresight, initiative,

capability, leadership ability were necessary attributes of any chief who wished

to maintain actual authority over the

tribe.

[107] A capable chief’s lead was

generally followed, but was not without question by the rest of the

rangatira class and the important

elders in the community.

[108] Those Chiefs

who were not “effective in the eyes of the people” were considered

“defective” or “hopeless” and were removed or replaced

for the purpose of all important

decisions,

[109] staying on perhaps only to

perform certain ceremonial or ritual

rights.

[110] Often the replacement of an

incapable or otherwise unrespected

ariki was a younger brother or nearest

male cousin on the father’s side and if no other heir on the

mother’s side.

[111] One of the reasons

for the ability requirement of Maori leaders is that chiefs retained

responsibility for acting as the guardian of ancestral heirlooms, and trustee of

tribal property.

[112] Those chiefs that were

successful in retaining authority and respect in their community were usually

possessed of great leadership qualities but also great

wealth.

[113] Wealth for the chief was

particularly important as his rank, prestige and authority depended on it.

Specifically, the chief’s ability to provide lavish entertainment for

visitors, disburse wealth among his followers, and to retain a large number of

personal slaves were central to his community

reputation.

[114] Despite the need to have

visibly more resources than other Maori, the position of chief did not represent

some great mass of wealth and on the whole the difference between chiefly

ownership and that of other community members was only one of

degree.

[115] E. Mana

and Tapu

Mana,

defined as life force, prestige, power, influence, and

authority,

[116] can be both inherited or

earned during life,

[117] or can be lost

temporarily or permanently through

contamination.

[118] The reason

mana is important is that those

displaying high levels of it are respected for being viewed favorably by the

kawai tipuna or revered

ancestors.

[119] In the sense that good

actions, ones consistent with Maori values and customs produced or increased

both individual and group

mana,

[120]

mana is somewhat of a karmic concept.

At birth, child inherited

mana from his

or her

kawai tipuna; then throughout

life his or her

mana was increased

through advantageous marriage, excellence in warfare, artistic prowess,

exceptional work-ethic, or expertise of history and Maori

custom.

[121] Abuse of skills or power,

laziness, carelessness, illness, poor harvests, and harm to others would

decrease one’s

mana,

[122]

as would contact with cooked food yield decrease in

mana by

contamination.

[123] Further, capture as a

slave—even a slave who used to be a chief—completely depleted

one’s

mana, leaving him with no

spiritual presence; as a result, slaves could handle cooked food and other

contaminated products since they had no

mana to

offend.

[124]

Tapu, defined as sacred,

restricted or prohibited, is a principle within Maori society which operates to

protect, prohibit and control the members by restricting certain activities and

behaviors.

[125] One way of explaining

tapu is as the “major cohesive

force in Maori life” as each person was “tapu or sacred,”

“each life a sacred gift” linking the living with the ancestors and

consequently the whole tribe.

[126] Further,

people and things become

tapu when

“imbued with the mana of the kawai tipuna,” bringing the thing or

person under the kawai tupuna’s protection and yielding tribal

respect.

[127] Maori feared breaching tapu not

just for the shame it would bring on themselves and the community but for the

possibility of sickness and other misfortunes that would result from disfavor of

the

kawai

tipuna.

[128] II. Maori

Legal System

A. Introduction

Lacking a written language,

Maori law is not codified, collected, or organized in the permanent way in which

writing cultures legislate. In fact, it is possible that the form the Maori

legal system takes derives from the lack of a written language. Instead, the

ideals that form the foundation of Maori laws grew into oral traditions and

manifested in sacred beliefs.

[129] Thus, the

Maori legal system is one based upon principles, not rules, a value-based system

deriving from Maori custom or

tikanga.[130]

These customs form the basis of the legal system, adding rationale and authority

to legal principles because of the spiritual foundation of the

tikanga.

[131]

One of the lauded benefits of a principles-based system is that Maori law was

able to adjust to changes in values without damaging cultural integrity, on the

whole a fairly flexible system.

[132]B. Ownership,

Property and Principles of Law

1. Ownership

Generally

Although terms such as

‘property’ or ‘ownership’ do not necessarily describe

identically analogous properties when applied to native communities, according

to Firth, the “essential factors... remain unchanged” though

“formed against a different cultural

background.”

[133] In fact, though Maori

vocabulary lacks a specific counterpart to the term

“owner,”

[134] this is not

evidence of a lack of the concept of individual ownership. Quite to the

contrary, their speech flows with ample examples of possessive language: In

speaking of stolen taro, a Maori women says “Ko ana taro nei, nana ake

ano, ohara i te tangata ke nana ere taro” meaning “those

taro were her very own (nana ake ano);

they did not belong to any other person (tegata

ke).”

[135] Further evidence of the

concept of Maori Ownership is evidence in the custom of labeling private

property items with a

tohu or

distinguishing mark.

[136] Despite Maori reputation for

communal living, single contemporaneous use items such as clothing, ornaments

and scents, weapons and personal tools like fish-hooks or spades were entirely

reserved for private individual use.

[137] In

addition to these privately owned items, other personal property included all of

a man’s movable items such as his home, fences and other small

items.

[138] However, since house furniture

did not exist,

[139] such other items were

small in number. Finally, it is interesting to note that as a general custom,

items of greater import in Maori culture were often

named.

[140] Examples of named items include

rare bird spears,

[141] ancestral Maori

canoes,

[142] feathers with special powers or

repute,

[143] special trees from which the

bark produced a rare dye.

[144] Such naming

signified importance, uniqueness and sometimes afforded the item a supernatural

mystique.

[145] 2. Acquiring

Personal Property

Firth illuminates that despite

personal ownership of these items, since women exclusively made the clothes,

such ownership trends do not account for the transfer from producer to

owner.

[146] By

creation:

Often, production or creation of

an item carried with it a strong presumptive right to its private

ownership.

[147] This was true in particular

for items available to any tribe member willing to put for the effort to make

such an item. For example, men who selected the wood, carved it and created a

tool with it were the sole proprietor of such creations; women who gathered

flowers or berries to make perfumes or oils were the sole owners of the fruits

of their labors, too.

[148]By

gathering or killing:

The fact that ones portion of the

cultivated crops was owned, also suggests, according to Firth, “some

process of the distribution of the fruits of

labour.”

[149] While it was also true

that anything made or caught by a “freeman” was owned exclusively by

him, if his superior, such as the village chief, were to ask for some of the his

catch, or for the use of his canoe, the owner could hardly refuse. This was both

because of respect for the superior and also because such gifts were customarily

repaid with interest.

[150] Finally, Firth

explains that although such food items gathered by a Maori in a solitary

expedition were regarded as his own private items, they were typically

incorporated into the communal supply of food for the family group or

whanau.[151]

By Exchange:

Exchange

[152]

was, however, an equally valid method of acquiring personal

items.

[153] Items such as the stone adze, a

feather plume or a greenstone ornament, and others involving more labor,

significant skill or rare materials were often traded rather than created. In

addition, since men depended exclusively upon the women in their

whanau for their clothing, such items

were also achieved through exchange of services within the Maori

household.

[154] By

inheritance:

Items of difficult manufacture

such as the bird spears of

tawa were so

highly prized that there were named and carefully passed from generation to

generation, father to son.

[155]3. Maintaining

Exclusivity

The exclusivity of ownership

for the Maori meant somewhat of the same thing as in our culture: for example,

to erect a home or dwelling hut on someone else’s property required

permission, and was otherwise a form of trespass which afforded the owner of the

land the right to exclude the trespasser at the time of his

choice.

[156] The right to exclude was only

superseded if there were witnesses who could testify to the original permission

being granted. Still, in reference to the communal nature of the Maori culture,

Firth emphasizes that land trespass probably did not apply to members of the

whanau.[157]

Additionally, for a Maori to grow crops on someone else’s land required

permission granted to him.

[158] Taking or

using without authorization one’s personal property was regarded as theft

and could incur serious punishment.

[159]

An additional, though unusual

method of maintaining private ownership of goods was to hide them; during the

1840s New Zealand travelers noted that Maori would sometimes return from

forest-concealed stores with food and other

provisions.

[160] However, Firth suggests this

was a result and reaction to instability and war, and not of common practice.

It has been claimed that the

small subset of privately ‘ownable’ items contrasts greatly with the

rest of items in Maori society which varied in their degree of communal

ownership.

[161] However, though the common

system of borrowing any number of owned items might appear to render these items

communal by virtue of the fact that permission to borrow was a formality not

often relied upon,

[162] such a conclusion is

not entirely correct: Much like the practices of the Cheyenne Indians, borrowing

without permission did not indicate lack of ownership but instead carried with

it the restrictions that borrowing happen only when the item itself was not in

use and that the item had to be returned upon the request of the

owner.

[163] Further, borrowing usually

required compensation which, if not by gift, was in the reciprocal ability to

borrow in such a manner.

[164] Still, borrowing without

permission was not a practice available between different ranking Maori. The

supernatural concept of

Tapu, which

always surrounded important figures in Maori communities, rendered all items

touched by such “men of

rank”

[165] fit only for his private,

individual use. Consequently serious supernatural harm could come to common

Maori who used such items.

[166] 4. Theft

and Lost Property

Though in many modern legal

systems the remedies for theft and robbery available to the victim are limited

to monetary compensation through civil suits, in Maori tribes even violent

physical punishments were reserved to and the responsibility of the wronged

individual.

[167] Maori custom generally

accorded the owner the right to punish the thief with violence and even death,

though non violent punishments were also

permitted.

[168] Interestingly, it appears

that theft from non-Maori or from a member of a different Maori tribe was not

regarded with the same severity and therefore was not likely to be viewed as

justifying the owner in violently punishing the

thief.

[169] In some instances owners were

content to negotiate for a fine or a return of the property rather than

resorting to violence.

[170] In one case, the

owner of a stolen mat announced his intention of “making war upon the

culprit and killing him” but was convinced through public discussion to

accept a canoe and a slave to call the affair

settled.

[171] Additionally, it seems that in

some informal manner, thefts of lesser valued items predictably resulted in less

severe reactions by owners. For example, the theft of firewood seems to have

been extremely common and only to have resulted in accusations and quarrels but

not in actual violence.

[172] Many anecdotes describing

instances of the owner killing the thief are also cases where owner caught the

thief stealing taro in one case and in another fish from the owner’s

net.

[173] So even though there are few

examples, it was still accepted practice in Maori culture that the wronged party

have the ex post facto right or option to kill the

thief.

[174] What is not clear is whether

there were often abuses of this system; since there does not seem to have been a

trial or other fact gathering institution, it is hard to tell how guilt was

determined if the party was not caught stealing and therefore whether or not

many innocent Maori were accused and punished for theft. Though in most cases

the enforcement of the punishment and the exaction of remedy was entirely

private, in at least one case there is evidence that the village chief mediated

the case between one of his own citizens and a European foreigner. The dispute

evolved because the European charged the Maori with the theft of one of the

former’s ropes. The Chief addressed the accused with

“

Nau tenei i tahae” meaning

“You have stolen this” and the man replied that it was true

“

Tika.” The Chief

pronounced that as a consequence, the thief had forfeit all his property to the

European “Kei te pakeha te tiganga o au mea

katoa.”

[175] Again what is unclear is

what the result would have been had the Maori man not admitted the crime. There

is no evidence of a further evidence gathering procedure to determine innocence

or guilt. Still, owing to the relatively even distribution of wealth, the lack

of severe poverty, and the Maori custom to help the needy, early travelers

reported few thefts even when their valuable possessions were left

unattended.

[176] When, as was often the case, the

owner did not catch the thief “red-handed,” or for some other reason

it would be inappropriate to apply a physical punishment, an owner could apply

supernatural punishments to induce the thief to either admit the crime or return

the property.

[177] The Maori believed that

certain spells when applied to an item that the thief touched or handled could

cause insanity or death unless the property was

returned.

[178] In contrast to stolen property,

lost items were considered the property of the

finder.

[179] The traditional American saying

of “

Finder’s keepers, losers

weepers” directly correlates to a concept in Maori tradition:

“

Ko te kura pae a Mahina”

meaning “it is the treasure picked up by

Mahina.”

[180] The saying refers to the

story of a man who found a red head-dress by the seashore which had been thrown

away by its owner. Mahina, upon finding it refused to return it to the owner and

in so doing established a rule of customary Maori law:

“

e kore e hoatu kit e tangata nana te

taonga” – “the owner cannot obtain it

again.”

[181] It seems that the only way

to regain one’s lost property once recovered by another was in a voluntary

trade and thus once lost was unlikely to be

recovered.

[182] 5. Inheritance

law

If a Maori man had no near

relatives or children, his portable possessions were buried with him and larger

items allowed to decay. Thus items of purely private ownership that were not

inherited were interestingly also

not

acquired by the

hapu or the

tribe.

[183] The case of a dispute that arose

between the Ngatipou and Ngatimahuta

hapus

(clans) describes, among other things, one of the customs of inheritance

when a couple had no children.

[184] In this

conflict, two clans disputed the ownership of an eel-weir (structures over

waterways from which eels could more easily be fished) on a lake mostly owned by

the Ngatipou clan. When a Ngatimahuta man married a Ngatipou woman, the

Ngatimahuta attempted to claim the eel-weir for their own tribe since the

Ngatimahuta man had been responsible for building the

weir.

[185] According to the inheritance laws

of the Ngatipou, however, since there were no children in the marriage, upon the

death of the man, the weir reverted to the widow’s eldest

brother.

[186] A conflict of law arose when

the Ngatimahuta Chief attempted to trace ownership of the area back seven

generations to avoid the Ngatipou claim to the

weir.

[187] Thus aside from demonstrating an

interesting law of inheritance, this also shows the custom that Maori chiefs

would take an interest in an item of personal property of one of their members

in order to claim that interest for the whole

tribe.

[188] In general, children, regardless

of gender each received an allotment of property upon a parent’s

death.

[189] Such an allotment could include

weapons, tools, clothing and other small items and were actually shared equally

by the inheriting offspring.

[190] Smaller

items of particular value such as dogskin cloak or ornamental greenstone,

however, would be inherited by the eldest son as the new head of the

whanau.

[191]

Larger items that were not easily divisible (the canoe, dwelling-hut, etc), were

held in common ownership by communal consent of the

children.

[192] As the eldest male received

certain property, women could also divest their property to their female

heirs.

[193] An interesting rule of ownership

held that the

tanekaha tree, from which

a rare clothing dye could be made, belong only to the descendants of the

original person to claim or be assigned such a

tree.

[194] The story of a particular necklace

called a

hangaroa illustrates the

flexibility of the rules of inheritance in Maori culture: Te Wahamu (a woman)

placed her

hangaroa around her

daughter’s neck shortly after birth. This item seems to have become the

daughter’s property upon the death of Te

Wahamu.

[195] Then when the daughter had no

children, she placed the necklace on her brother’s daughter with whom the

necklace was buried since she died without

issue.

[196] Though this story perhaps better

illustrates the practice of ownership rights associated with the giving of

gifts, it clearly demonstrates how such ownership passed over time through

changes in generations.

It seems to have been common

practice in Maori inheritance for the males of a family to inherit certain items

and the females other items. Usually the division related to the different

gender roles and responsibilities common to a tribe. In one tribe, it was

customary for the females to inherit the rat-runs while the males would take

over the bird-snaring trees.

[197] What is

interesting is how, without a written language, written legal system or any

formal courts, boundaries of ownership were maintained. It seems that as

children Maori would learn the locations of the boundaries what their family

owned so as to be able to pass on the knowledge to their own

families.

[198] Additionally, when a man

married a woman of a different

hapu and

came to live within her village, though he had no ownership rights to her land,

his children would inherit her lands as well as his which were located within

his

hapu.[199]

In spite of scrupulous care that

was taken to mark and differentiate between different property, including the

custom of making all inheritance divisions public knowledge, some inheritance

disputes did arise.

[200] In response to such

conflicts, complaining family members could address the community for a decision

to settle the affair, the opinion of the whole village or sometimes tribe acting

as an informal court of appeal.

[201] Without a written language,

wills were made orally in a formal and solemn speech usually when an aged person

was near death.

[202] And, much like in other

cultures, the decedent’s wishes were powerful and regarded as binding upon

his relatives,

[203] the eldest son usually

being the executor of such a will.

[204] An analysis of Maori inheritance

customs would be incomplete without reference to the rules regarding adopted

children. In much the same way as current American law operates, once final, an

adoption truncates all inheritance rights of the child from their biological

parent and attaches the child to the adoptive parents for all legal

purposes.

[205] What is particularly

interesting about this is that the purpose of the adoptions was, as stated in

the earlier section on adoption, to effectuate connections with distanced parts

of the tribe or family. It seems strange, then that while attempting to bring

distanced families closer together, the inheritance rights were so strict.

6. Maori

Communal Ownership

To the degree that it is

possible, I will attempt to draw a distinction between property owned at the

household level as compared to those items owned by the village as a whole. The

difficulty in this distinction derives from the social organization of a Maori

tribe which is comprised by aggregating the families or

whanau into larger kinship groups or

hapu which, in turn, were combined to

comprise the villages and then the

tribe.

[206] Consequently,

whanau property

ipso facto belonged to the

hapu and therefore also to the entire

tribe.

[207] Household

Property

The most important communally

owned property is arguable the dwelling house or

whare in which the

whanau, closely related family members,

lived together.

[208] Another important item

that was owned communally at the family level was an eel-weir. Eel-weirs that

belonged to families were smaller structures built over smaller streams and

creeks from which they fished for eels.

[209]

Other items that were owned at the family level include

taha or gourds with carved mouthpieces

or large enough to contain preserved birds.

Taha were considered very valuable and

were therefore protected and maintained for generations, being passed down the

female line.

[210] Aside from the limited

amount of food supplies that the

whanau

might reserve for their own consumption, very few other items were considered

exclusively the property of the

whanau.

Among these were the few items contained within the dwelling houses including

sleeping mats, water and food supply containers, and oven

stones.

[211] Additionally, for water

transport or fishing in tribes living near waterways,

whanau often owned one or two

waka tiwai or small canoes seating

seven or eight.

[212] As for rights of usage

among the family members, it seems that any family member had an equal right to

use the canoe even if only one member had been responsible for making

it.

[213] It is likely however, that where

conflicting claims to use such canoes developed there was some customary family

hierarchy to determine whose interests came

first.

[214] When it came to non-water

acquisition of food, a number of different levels of ownership were common:

Though the cultivation of the land was generally done communally, each family

had a small plot of land divided out of the communal field and marked by stones

or pathways.

[215] Another common method of

food collection was the erection of rat-runs which if small could be the

property of simply one

whanau. If

large, though, rat-runs might belong to several

whanau or even to several

hapu.[216]

Village

and Tribal Property

Like the eel-weirs that families

owned, when bigger ones were constructed over large rivers, they required heavy

timber and many Maori to erect and therefore became village communal

property.

[217] Further, much like the smaller

family owned canoes, larger war-canoes and sea-going vessels belonged to the

village and were for communal use even if in name they were said to belong to

the village chief.

[218] Another example of

the blending of personal and tribe property is the aforementioned custom that

village and tribal chiefs would contest property disputes between and among

tribes on behalf of the personal owners’ property

interests.

[219] Another more communally held

property was the village meeting house which was regarded as the common property

of all the village inhabitants and was always built by the villagers’

joint labor.

[220] In fact, even if the

village chief provided more funding for its construction, he was not considered

to have greater ownership than any other village member. Finally, items of

cultural or supernatural importance were usually held in the private ownership

of tribal leaders.

[221] However, it their

importance related to the tribe as a whole, they were instead held in a sort of

trust by each subsequent chief and were on occasion displayed for the admiration

of the villagers.

[222] C. Maori

Land Ownership

1. Maori

Attitudes on and Relationship to Land

Although different tribes, iwis

and hapus viewed specific portions of land as being collectively theirs, land

was less a commodity than the basis of identity, the foundation of the tribe and

only owned in the sense that it belonged to the community, equally shared among

the living, dead and those yet to be

born.

[223] This view of land as a

“source of identity” derives from custom: Maori principles of land

inheritances hold that through genealogy or

whakapapa, Maori groups establish and

maintain control over the land on which they live and

secure.

[224] Land possession and maintenance

are of the utmost importance to Maori principally because it is through the land

that the living are connected to their

tipuna and also to their future

descendants for whom they care for and hold the land in

trust.

[225] 2. Acquiring

“Title” or Rights of Usage

New Zealand, before its European

discovery, was a land divided tribal into territories over which each tribe

defended their rights through force.

[226]

Thus in a general sense, Maori land acquisition is a process of title by

conquest “

te rau o te patu”

and one’s title is as good as one’s ability to keep one’s land

exclusively for one’s own use.

[227]

This, however, is an oversimplification since even those attempting to take or

retake land by force went to a good deal of trouble to uncover some ancient

action giving them claim to the land.

[228]

Thus, in essence there are three steps in achieving title acquisition: conquest,

discovery gift exchange begin the process; occupation cements the first step and

ancestral right strengthens the claim.

[229]

Land attained through conquest

in war was termed

whenua raupatu so

that those acquiring the land did not forget its original

owners.

[230] Otherwise, land could be

acquired if it was discovered unoccupied in what was called

take

taunaha.

[231] The third method of

acquisition through a gift of land was called

take tukua and usually was in order to

recompense for infidelity on the part of a member of one’s

hapu or

iwi.

[232]

Any and all of these methods required occupation to make them legally effective

since unoccupied lands are considered acquirable through

occupation.

[233] Finally, when a group

occupied an area over which they had

take

tipuna (ancestral right), Maori universally recognized their title to the

land.

[234] The

take tipuna was established by a

recitation of one’s genealogy and line of descent, though no mention is

made of how this was authenticated.

[235]

An important aspect of acquiring

legal title was proof of occupation. According to Maori custom, there were five

main methods of proving such ownership: first, if present, one could point to

sacred mounds, stone markings or other identifying markers placed on the land at

the first settlement and upon which were indications of the genealogy and

ancestry of the owners. Further, one could look to other types of markers, newer

ones, such as on trees and rocks, burial cites and markers. Secondly, occupation

could be established if recitation of the genealogy or

whakapapa made reference, as was the

custom, to important places in that groups’

history;

[236] it was common for

iwi oral history to include prominent

landmarks and the stories of the ancestors who had acquired them and lived

there.

[237].Third,

establishment of a village of either

kainga or

pa presented clear authority for occupation of that land. Fourth,

occupation could be shown through use of natural resources such as eel traps,

fishing, rat-runs, gathering cites, and areas of cultivation. Finally, evidence

of gifts given of birds or trees present on the land and things may therefrom

could help establish a claim of

occupation.

[238]3. Land

Transfer

For many reasons intrinsic to

Maori culture and spirituality, land transfers outside of conquests were very

uncommon.

[239] For one thing, the importance

of

tipuna in tribal life meant that

natives of a particular land were often reluctant to leave, particularly in

light of the sentimental and spiritual value of tribal burial grounds and

important landmarks that formed part of the

iwi’s

whakapapa.

[240]

Another reason for static land ownership was that families could not sell or

exchange their own lands because they were subject to the

“over-right” of the

iwi in

whose interest is was

not to allow

strangers or other tribes to live in their

villages.

[241] Such over-rights created

another impetus towards endogamy because marriages outside of one’s

hapu and

iwi would give strangers or outsiders

access to tribal lands, an outcome which often produced legal

disputes.

[242] When a

whanau or

hapu did wish to alienate their land,

the

iwi chiefs had veto power; however,

it seems that the other rights inherent in the land ownership balanced out the

chief’s placing each legal interest on equal

footing.

[243] Apparently, though rare, land

could be alienated by gift; circumstances leading to such gifts were usually of

some type of the following: tribal peacemaking gestures, compensation for

breached

tapu, compensation for murder

or those killed in battle, damages for adultery, contribution to new marriages,

contribution to desperate relatives, and in some cases as a dispute resolution

settlement.

[244] Thus, in one instance after

the end of hostilities between two tribes, the chief of the Kawiti tribe gave to

those he had been fighting a large piece of land in the Bay of Island district

saying “The only payment I can offer for your dead is the land on which

they fell—namely, Kororareka. I am about to leave this place forever; and

henceforth you must consider this land as

yours.”

[245] Another case illuminates the

negotiation involved in exchanges of land for goods, demonstrating the method by

which parties to a cession of land came to a mutually agreeable price: When the

Ngati Kahungunu

iwi wanted to buy land

from Te Rereaw and his people, Te Rerewa explained that his people’s lands

would “not be parted with for [their] garments and weapons, but if it were

the bowl of [their] ancestor then indeed might an exchange be effected.”

[246] As the Ngati Kahungunu had come in four

large canoes, and as they understood that Te Rerewa and his people wished to

move from the North Island to the South Island, the Ngati Kahungunu agreed to

exchange their canoes for the land Te Rerewa was leaving. But, because the land

was considered more valuable than the canoes, the Ngati Kahumgunu contracted to

build Te Rerewa’s people three more canoes in exchange for being shown

the location of a

totara

forest.

[247] In conclusion of the

transaction—in what seems to have had both practical and ceremonial

importance—the Ngati Kahumgunu were directed to a hill top from where they

learned the lay of the land and were informed of the important landmarks, their

names and functions.

[248]D. Utu

– the Principle of

Reciprocity

Utu

is the principle in Maori culture for maintaining balance, harmony, and

equality, and as such operates as a form of restitution, aiming to restore the

parties involved to their former position or to bring both parties to equally

better relative situations.

[249] One of the

ways in which

utu creates serious

obligations on the part of an individual or group is when, as is often the case,

the

mana of an individual or a

community depended upon an action of

utu; it seems that to restore

mana, an

utu response had to represent more than

simple reciprocity, requiring some gesture greater than an act of

restitution.

[250] Depending upon the

situation, a proper

utu response could

entail a vengeful action, but otherwise could be a reward, an exchange of goods,

an exchange of services, or even an insulting, offensive

song.

[251] Further, different situations

required different timelines;

utu could

be necessary immediately or over generations, so long as eventually a balance

was restored.

[252] Another aspect of

utu that varied with the situation was

the method of determining the exchange rate: in determining the value, price or

amount needed for an appropriate expression of

utu, many of Maori cultural values

would be taken into account. It seems that aside from practical value,

aesthetics, social usefulness and tradition offer certain comparative standards

by which exchange value was determined.

[253]

In addition,

utu was commonly

understood to require a response of greater value than the harm or gift done to

or for the imbalanced party. Failure to assess an exchange or revenge of greater

value could result in a lowered

mana,

though it was up to the receiving side to judge whether justice had been

done.

[254]

1. Transfer

of Goods in Warfare

In general, goods seem to have

changed hands in much the same way as land did: by acquisition through

successful warfare, through

muru

(custom of recompense), and through exchange of

gifts.

[255] And although many good changed

hands by way of war, the primary motives for such wars were land disputes,

conflicts over women, intertribal insults and the like, not the pursuit of

physical riches.

[256] When a tribe captured a

village or fort in battle, all of the goods of the community became those of the

captors. Similarly, the weapons of dead warriors belonged to their slayers. In

several instances, negotiations to give a valuable weapon on the part of

warriors about to be slain to the impending killer were often received with

agreement and reprieve.

[257] 2. Utu

Retaliation for Hostility

Since

utu as a principle required that

injuries had to be avenged, insults compensated, and balance in general

restored, bad acts against other Maori had significant consequences somewhat

proportionate to the wrong committed.

[258]

General retaliatory actions consistent with

utu created a never ending cycle of

reciprocity because of the constant need for relationships to be in a natural

balance.

[259] And, though retaliation for

quarrels or revenge for spilt blood was required, it could take two or three

generations to achieve; Apparently the mechanism for remembering

utu responsibilities was that the

injurious actions would be woven into the traditional songs and dances of that

particular community so that the current generation would be held accountable

for restoring balance once again.

[260]

Legitimate reasons to wage war for

utu

compensation included, adultery, murder, spousal abuse where spouses were of

different hapu, breach of tapu, to counteract other tribes’ territorial

encroachment, and to revenge on other communities for prior defeats in

battle.

[261] And, although provoking other

communities with whom one was not at war would result in a decrease in

mana, those who were enemies could gain

mana by provoking

utu through insult, or abuse of

tapu.

[262] To that end, enemies kept detailed

lists of past offenses, particularly in light of the requirement for

intensification of

utu responses over

time.

[263] And although it would seem that

such intensification of violent responses would end in indefinite chaos, such

disputes could be ended by gift exchanges, peace-making fests, land transfers

and, most definitively the offer of a intertribal marriage; the “peace

brought about by women is an enduring

one”

[264] because an intertribal

marriage, particularly between high-born members of the warring tribes, brought

about a permanent peace settlement since they would now be related by close

kinship bonds.

[265]3. Muru

and

Whakawa

One specific

utu protocol is called

muru. A very specific and ritualized

way to attain

utu,

muru could only be made by those of a

fairly close relation to the offender and seems to be reserved for situations

involving people of consequence, and actions that were sufficiently relevant to

the tribe as a whole as to necessitate

intervention.

[266] Unlike general

utu, a

muru was an isolated incident,

internally initiated to restore the

mana of the individual and his or her

kinship group.

[267] Further, muru could be

instituted for accidental as well as intentional transgressions because the

transgressor and his or her “relatives were judged guilty of negligence in

allowing the accident to take

place.”

[268] Actions constituting

muru ranged from hand or stick beatings

for serious crimes such as accidental death to compensation in

property.

[269] For most offenses, a

plundering party was formed and to raid and take away all of the

offender’s moveable property and that of his or her

family.

[270] And, while such punishments

could be harsh and leave the offending parties with no belongings, the

muru was accepted as a way to nullify

the guilty and restore their

mana.

[271]

For that reason, and because reciprocal response would have meant bringing harm

to one’s own tribe,

muru were

close ended.

[272] The

Muru Protocol: Before a

muru was

instituted, the offense was the subject of a detailed discussion and debate

called a

whakawa.

[273]

Whakawa proceedings are analogous to a

trial and involve a great deal of

formality.

[274] Further, the process involved

an accusation of guilt and an investigatory phase out of which a decision or

judgment is determined.

[275] Factors

affecting the outcome of the

whakawa

included the status of transgressor, the status of the injured party,

relationship of the parties, the customs that were offended

(

tikanga), the nature of the offense

(intentional or accidental) and the involvement or intervention of the elders

(

Kaumatua).

[276]

Some

whakawa are small meetings between the

parties to the conflict and their immediate

whanau in which an agreement is reached

to end a dispute.

[277] More often, however,

whakawa involved much of the village,

and quite frequently are intervened in by the

Kaumatua or respected elders of the

tribe from whom the parties draw on for wisdom, guidance and usually a judgment

in the case.

[278] The community involved is

expected to take part in dispute resolution process and to defer to the

Kaumatua’s

judgment.

[279] Once the decision to go

forward with a

muru has been made, the

whakawa must determine what size

‘plunder party’ to send; the larger the party, the greater the honor

of the offender since the party size was directly correlated to the

community’s assessment of the transgressor’s

mana.

[280]

In some cases, the plunder took place more as a voluntary set of gifts from the

offender’s tribe to the offended party: one case involving a

muru to the

whanau of an adulterous woman was

described as follows. “Our leaders made fiery speeches accusing the local

tribe of [sexual misconduct]... punctuating their remarks with libidinous

songs” and after the chiefs admitted fault on behalf of their tribe,

individuals came forward “to lay ... before us in payment... jade

ornaments, bolts of print cloth[,] ... money [in pounds,]... horses and

cattle.”

[281] Apparently the end of

such an exchange could be concluded by the parties rubbing noses and the

transgressors hosting a large, entertaining

feast.

[282] The effectiveness of

muru depends upon community respect and

acknowledgement. The deterrent potential of a

muru derives from the fact that the

punishment applies to the whole kinship group and not simply the individual

transgressor.

[283] Further, even if

mana were not considered important, the

threat of

muru would probably deter

transgressions because of the potential material loss of violent punishment

inflicted upon the transgressor. And, despite the lost property or physical

punishment,

muru was seen as the

natural consequence of many actions, even those that were unavoidable. For

example, a leader of a war party might be subject to a

muru of beating as consequence for

those of his own party who died during the battle and as an expression of the

grief of their relatives. In much the same way that other

muru were met, such a war party leader

would accept the beating as an honorable consequence of his position, a

restoration of balance and equilibrium for the deaths under his

watch.

[284] 4. Gifts

and Gift exchanges

One of the most important

rituals in Maori society was that of the gift exchange. Gift exchange took

primarily two forms: one for economic gain, the object being to obtain a needed

or desired item of practical function from the exchange; the other for

ceremonial purpose, a social gesture of goodwill being the primary

function.

[285] In fact, the gift exchange was

the most common type of Maori contract, in which a gift giving necessitated a

return of equal or greater value.

[286] The

actual items exchanged varied a great deal and could range from physical gifts

such as tools, ornaments, and building materials to the exchange of services or

hospitality or meals.

[287] Typically, the

economic exchanges were for food items whereas ceremonial gifts were most often

greenstone heirloom, particularly at

funerals.

[288] And, just like other processes

governed by

utu, gift giving was a

cycle, a never ending attempt to achieve a balance and equilibrium between

individuals, groups and even with the natural

world.

[289] The general Maori attitude

toward gifts was that “it was always better to give, because [one knew

that gifts] would come back:” a greenstone heirloom once given would often

be returned to the giver’s family in some later

generation..

[290] Further, the anticipation

of receiving something of greater value at some later date made gift giving

quite agreeable to both parties.

[291] One

reason for giving a more lavish return gift was to increase the giving

community’s

mana. And, even

though the gift of a greater value than the recipients could repay would

humiliate them and subordinate them, such a gift still resulted in the growth of

the givers’

mana and,

incidentally a loss of

mana to the less

wealthy receivers.

[292] As the gift-giving

cycle continually escalated, eventually, the goal was to develop a social

relationship tantamount to an alliance in which, through the trust built up over

generations of exchange, each community could rely on the other in times of

need. Once such a rapport had been established, failure to give immediate aid

might result in reprisal.

[293] To ensure that

utu was followed, various mechanisms

operated by virtue of Maori

tikanga or

custom.

[294] The most influential constraint

on the system was the notoriety imbued upon those who did not make the

tiki or correct

response.

[295] Such dishonor would affect the

individual and family reputation creating a disincentive to do any future

exchanging with that group, a severe consequence when certain items could only

be attained through trade.

[296] Another

method for maintaining the reciprocal balance of

utu was belief that supernatural

punishment, particularly in the form of physical handicap or illness, would find

those who did not reciprocate.

[297] The way

that the supernatural punishment functioned is illustrated by the following

explanation by a Maori man named Tamati Ranapiri:

“Suppose

that you possess a certain article and you give the article to me without price.

We make no bargain over it. Now I give [it] to a third person, who after some

time ... makes me a present of some article. Now that article that he gives to

me is the

hau [vital and supernatural

essence] of the article I first received from you and then gave to him. The

goods that I received for that item I must hand over to you...[because] were I

to keep such equivalent for myself, then some serious evil would befall me, even

death.”

[298]Finally, although many of the

supernatural punishments could be warded off by particular witchcraft

precautions, the damage to reputation by failure to comply with

utu was immediate and had no magical

remedy.

[299] Since the gift exchanges never

involved barter in the sense of immediate negotiation as to the return price for

the item given,

[300] it is hard to assign

specific values to the items exchanged.

[301]

And, it might have also been very difficult to have satisfactory exchanges had

it not been for the common practice of hinting at the object expected or desired

in return.

[302] The subtle form of the hint

not to be misunderstood, saying “I am very fond of that” was

tantamount to an outright request for

it.

[303] In one instance, Te Reinga a man of

Kaitaia was so “greedy” a “gourmand” that whenever a

person carrying food passed him, he would exclaim his fondness for that item

such that they could not but give him some. Over time, his notorious abuse of

utu resulted in a war party slaying

him.

[304] Firth’s analysis of this

wittily suggests that Maori principles favored killing someone over injuring his

feelings by a refusal to share in this

manner.

[305] Perhaps the explanation is not

quite so counterintuitive: it seems entirely consistent that Maori would not be

able to refuse such a request because it would lower their collective

mana. Further, war parties were usually

initiated as a result of

muru. If such

were the case, then the dispute would have been well known and discussed in the

community. Generally, through

korero

(dialogue) disputes could be settled by some compromise between the parties. It

is likely that if Te Reigna had been willing to counter-gift those from whom he

had received food, his life and

mana

would have been spared.

Another way that gift exchanges

came to be satisfactory to both parties without a negotiation process was

through repetition of exchange for the same

items.

[306] Extra-communal exchanges commonly

involved one type of food for another: thus coastal inhabitants gave seafood

while inlanders provided with birds, eels, rats, and other items collected from

forest areas.

[307] Intra-communal exchanges

more commonly involved services or goods made by specialists such as difficult

to make tools.

[308] III. Conclusion.

In the webbed book,

A Glimpse into the Maori World, a

serious of in depth case studies derived a long list of some principles that

govern Maori legal interactions.

[309] Some of

the more central ones are listed below to help sum up the concepts, values,

ideology, philosophy and doctrines governing relationships in the Maori world.

• Kaumatua

(elders) act on behalf of the collective group when a transgression of

tikanga (cultural values) affects

others in the community. Because Maori society is communal, the collective group

must take responsibility for the actions of individual members, good or

bad.

• Individuals

represent their whanau,

hapu, and

iwi and collective rights often

supersede individual ones in the same way that

hapu rights

supersede whanau ones.

• Parents

and the whanau are responsible for

protecting children from spiritual, physical, mental or emotional harm.It is the

responsibility of the whanau to teach

children the Maori tikanga and the

responsibility of the kaumatua to teach

young adults appropriate behaviors dictated by the

tikanga.

• Gifting